Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) is revolutionizing how governments operate, but one side of its potential may not be sufficiently emphasized. At its core, DPI consists of digital systems that facilitate essential government functions (Metz et al. 2022). These include digital identity systems, payment interfaces, and data exchange platforms. Countries like India and Estonia, along with emerging success stories in the Global South (Chinyama et al. 2023), have demonstrated the transformative potential of these systems. Let’s explore how implementations of DPI could leverage new analytics engineering developments to enhance public service delivery and policy making.

From Government Transactions to Government Intelligence

While zooming in on DPI’s data exchange capabilities, Eaves and Sandman (2023) explain that these systems “allow public and private sector organizations to securely share information – with individuals’ consent – to facilitate the delivery of services”. This infrastructure standardizes how information is collected and shared, making it easier for individuals to access services and for businesses to improve their operations. The full quote is worth reproducing here:

“Data exchange capabilities allow public and private sector organizations to securely share information – with individuals’ consent – to facilitate the delivery of services. Public sector data sharing is often technically challenging, and even when possible relies on a patchwork of agreements that impede accountability and transparency. Standardizing how information is collected and shared by public institutions can make it easier for individuals to gain access to services. For example, individuals can use data exchange to share their health records with their doctor and pharmacist or their income level with social assistance and tax administrations. Businesses can share data about goods and services they administer to improve supply chains. X-Road, Estonia’s data exchange system, is a good example.” (Eaves and Sandman 2023)

While technology-agnostic by design, DPI frameworks reflect a pattern seen in pioneering implementations that have primarily focused on transactional data flows - as illustrated above. Without explicit consideration of analytical capabilities, this historical emphasis might lead new implementations to focus too narrowly on transactional systems.

In my own country, Cabo Verde, where significant progress in DPI development has been made, our systems excel at handling transactional data - recording civil events (births, marriages, deaths), processing government payments (taxes, fees, benefits), or issuing official documents (licenses, permits, certificates). Yet their potential for deeper analysis remains largely untapped, particularly in their ability to generate actionable insights from this wealth of data. I remember, for instance, a conversation with one of our election system administrators, years ago, that revealed a surprising gap in our otherwise comprehensive digital election system in Cabo Verde: we weren’t tracking individual voter turnout. Simply recording that someone voted (not their choice) could inform targeted policies to address our significant abstention rates. Here’s a clear case where basic analytics, with appropriate privacy safeguards, could strengthen democratic participation. The system focused on managing the process, and did it very well, but missed opportunities for continuous improvement through data-driven insights.

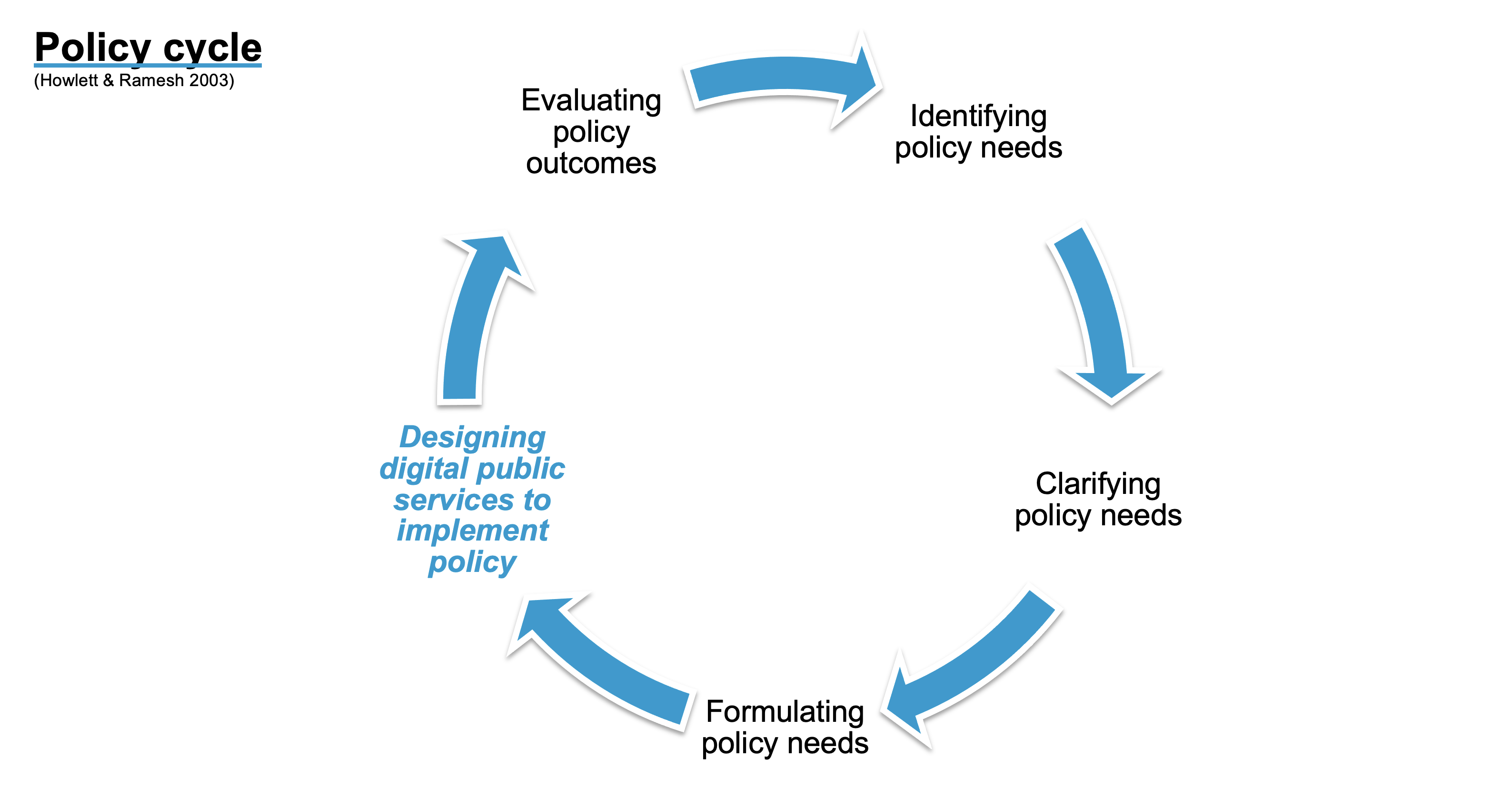

The implementation of DPI offers an opportunity to think beyond digitalizing service delivery mechanics. After all, these systems operate within the broader context of the policy cycle (Howlett and Ramesh 2003), where service delivery is engineered to achieve specific policy goals:

The policy cycle above illustrates how service delivery quality depends not only on execution but also on design and evaluation. The effectiveness of public services is shaped by each stage of this cycle. For example, a digital civil registration service isn’t just about efficiently recording births. As Fu and MacFeely (2022) note, without accurate civil registration data, governments also face significant challenges in planning healthcare, education, and social services.

Including analytical capabilities in these systems from the starting architecture could enable more than just improved record-keeping - it might allow for demographic pattern identification, service demand forecasting, and early detection of public health trends. Therefore, its success depends on how well it is designed to meet identified community needs, how effectively it’s implemented across different contexts, and how its outcomes are evaluated to ensure it’s achieving intended policy goals. This interconnected nature of the policy cycle demonstrates how valuable analytical capabilities can be at each stage, potentially helping governments better predict, measure, and understand policy impacts.

How Analytical Capabilities in DPI Implementation Could Transform Policy Research and Implementation

In a recent analysis of policy research and implementation in developing countries, Opalo (2024) identifies several critical needs: building knowledge production systems closer to implementation, re-empowering government policymakers, and focusing on broad-based economic transformation. These objectives could be supported by explicitly incorporating analytical capabilities when implementing DPI.

By incorporating analytical capabilities from the start, DPI implementations could create a bridge between day-to-day operations and evidence-based policymaking. This bridge can be materialized through a continuous feedback loop that brings knowledge production directly into the policy implementation process. For instance, analytically-enabled civil registration systems could help policymakers evaluate outcomes within their local context, while feeding insights back into planning processes for education, healthcare, and social services.

Rather than relying solely on isolated program evaluations, integrated analytical systems could provide granular, context-specific evidence of what works in implementation. By tracking broad economic indicators alongside service delivery metrics and policy outcomes, these systems could empower policymakers to understand complex interactions and support more transformative policy approaches—all while reflecting local institutional capabilities and constraints through continuous data collection and analysis.

Building the Bridge: Integrating Service Delivery and Policy Analytics

Modern data engineering offers promising tools that could support this approach to how governments use data. This isn’t just about incremental improvement - it represents a potential paradigm shift in how governments can understand and serve their citizens. However, implementing DPI with strong analytical capabilities isn’t straightforward. It requires bridging two worlds that rarely intersect: government IT and cutting-edge data analytics and engineering.

Supporting both service delivery and policy improvement requires handling two distinct types of data workloads. Transactional workloads, which form the backbone of day-to-day government operations - like recording birth certificates, processing licenses, or managing tax payments - require systems optimized for real-time processing of individual records with high reliability and support for many concurrent users. Analytical workloads, on the other hand, examine this administrative data in aggregate, often processing vast amounts of historical data, to understand patterns, evaluate policy outcomes, and support evidence-based decision-making.

Traditionally, these different needs have led to separate data architectures - transactional databases optimized for fast reads and writes of individual records, and analytical databases optimized for processing large datasets. Data teams often find themselves struggling to bridge these two worlds, trying to piece together solutions that can both efficiently deliver services and effectively support data-driven decision making and evaluation.

Addressing this challenge in DPI implementation requires careful consideration of data flows and system architecture. While common DPI implementations often prioritize administrative data, generated by public information systems and backed by transactional databases, enabling sophisticated policy analytics requires this data to flow seamlessly from transactional systems into data lakes that analysts can leverage for advanced analytics using specialized analytical databases.

While DPI implementations have matured to service transactional needs, there’s an invaluable opportunity to explicitly emphasize and plan for analytical capabilities from the start. Modern data systems approaches offer promising new solutions in this direction. Emerging architectural patterns like composable data systems(Data 2023; McKinney 2024), multi-engine data stacks(Hurault and Chung 2024), and portable data lakes(Brudaru 2024), to name a few, might help bridge the gap between transactional and analytical public data systems.

Recent advances have made sophisticated analytics more accessible and manageable than ever before. The technical details of such a claim deserve their own discussion. I’ve been exploring these possibilities through a proof of concept focused on creating scalable, multi-engine data processing pipelines for country-level public data (see here). A forthcoming post will detail the implementation considerations being explored with this approach.

What Next?

If you’re in government tech, consider exploring how modern data processing approaches might apply to your specific challenges. If you’re a data engineer, consider how your skills could be applied to public service. And if you’re a policymaker or engaged citizen, consider asking questions about how your government uses data to make decisions. What analyses might be possible with data already being collected? Consider advocating for investments in not just collecting data, but in extracting greater value from it.

Digital transformation isn’t just about making governments more efficient. It’s about making them more responsive, more equitable, and more effective at improving people’s lives. The future of government could be increasingly data-driven, responsive, and intelligent. By thoughtfully implementing DPI with analytical capabilities enabled by modern data engineering, we might be able to make that future a reality. Let’s reach across the gap and continue this important work.

Acknowledgments

Post card photo by Robert Katzki on Unsplash

References

Citation

@online{lima2024,

author = {Lima, Mirian},

title = {Beyond {Transactions:} {Analytics-Enabled} {Digital} {Public}

{Infrastructure}},

date = {2024-10-31},

url = {https://mirianlima.github.io/posts/2024-10-31-dpi-composable-data-systems},

langid = {en}

}